Racial Profiling and Preconceived Notions in Healthcare in relation to Patient Care and Safety.

Racial profiling in hospitals is a patient safety issue.

Television programmes be they soaps or american medical shows, have always played a part in highlighting topical issues that are occurring in society in a more relatable way to the general public. We have seen EastEnders tackle issues around cancer, sexual consent and rape culture, schizophrenia, New Amsterdam and the opioid crisis, just to mention a few. Medical firsts have also been premiered in television medical shows and later we have been made aware of real life stories of those who have undergone these pioneering procedures.

The issue of race and its influence on healthcare provision and access is now coming to the forefront, especially after the Black Lives Matter protests and the healthcare disparities that have been laid bare by the Covid19 pandemic. This has come as no surprise to most BME patients and healthcare workers who have long known about these issues, raised concerns about them only to have nothing done to address them with business carrying on as usual.

The Good Doctor is an american television medical show, that in one of their recent episodes( season 4, episode 9), dealt with the issue of racial profiling in current medicine practice as well as forcing one of their resident doctors to take a hard look inwardly and confront their own preconceived notions. Claire, the doctor in question had been called to the emergency room to attend to a patient who happened to be a black woman who had experienced a cardiac event. Zara, the patient was on anti-hypertensive medication and was insistent that she was taking them as prescribed and had even brought them along with her, only in the confusion, she couldn't find which pocket she had placed them in. Claire on the other hand considered Zara ‘loud and messy’ and did not believe that she was compliant with taking her medication(which Zara did find eventually).Instead she used a pattern- processing technique that she had learnt in medical school which supported her case that ‘loud and messy’ black people always lied about their compliance and went ahead and administered an ACE inhibitor to try bring down Zara’s blood pressure which in turn led to complications with Zara needing open heart surgery as a result! Zara later learns of Claire’s assumptions based on racial profiling, requests that she is taken of her case and later confronts Claire , who feels afronted that she would be considered racist! You see, Claire was a black doctor, who had based her assumptions on her own experiences of being racially profiled and constantly having to prove herself to get to where she was and ‘loud and messy’ Zara was everything she was trying not to be so as to fit in a predominantly white environment. This was also the experience of a fellow non white doctor. Basically, they had to check their blackness at the door. How many times as a black nurse or patient have you been required to or felt the need to “check your blackness at the door” for you to get where you need to be or treatment. I know i have and this episode got me reflecting on instances during my work where racial profiling and or preconceived notions has been at play and where it has been framed as ‘the problem patient’ and my role if any in those scenarios.

Working on an acute medical ward, especially if it is a short stay one, you get to see familiar faces often in terms of patients and at times predictions can be made as to when they are likely to come back. These predictions could be based on certain trends illnesses take based on weather patterns and seasons and others are based on compliance and social issues. This is common amongst patients living with long term conditions, who more often than not have borne the brunt of cuts in services, speciality ward closures which in turn means they are in hospital more times than they would like.

Working on one such ward, we often had patients who had come in after a flare up of their conditions and subsequently admitted to the short stay unit. One such group of patients were those who suffered from sickle cell disease, a young demographic, who were trying to live their lives the best way they knew how. Somehow these patients had been labelled as problem patients, so much so that as soon as you walked through the door on your way to handover, you would be briefed on how many had been admitted or were on their way to the unit. One particular patient, got double the warnings and lookout calls from management. All this was because of pain management , what the doctors and nurses thought was best for the patients( little or no opiods) and what the patients rightly so argued was not working for them( lack of opiods or hostility towards them when opiods are requested). The scene as usual was set, the nurses and doctors caring for these patients already on the defensive and on the lookout, tensions palpable waiting for the so called problem patients. The patients on the other hand are also on the defensive and know that they have to fight again to get the pain relief and care that they deserved. This was a constant, ongoing scenario and we were more often than not so caught up in the battle of wits that we forgot to see the patient, the person behind the label. Yes we doled out care and medicines as prescribed, ticked the required boxes, freed up beds as fast as they were needed, often under very stressful and pressurised conditions not to mention short staffed. Care became automated, assembly line like.

Several studies have now shown that there is a great racial bias in pain assessment and management when it comes to black patients. Black patients, like these sickle cell patients are systematically under-treated for pain, especially when it comes to getting an opiod prescription. This was compounded by the fact that almost all speciality wards had been axed and closed across NHS trusts, where they would have received specialised care from a team that understood their disease process. Instead they were sent into a system that although provided care, it was care that was conditional and didn't meet their needs at best and was combatative at worst.

Years later, working within a specialist clinic, I had the chance to interact with one of the patients who had been labelled as doubly problematic when I was on the wards, from management to staff on the ground. The difference this time was that the management I worked under were aware and against the bad reputation this particular patient had been given all over the hospital and always made a point of mentioning the fact that, the patient was a young person, who was living their life despite their long term condition and the many complications( medically and socially) that came with it. In other words he made sure we saw the person behind the condition and focused on the person. He re-framed the equation from ‘problem patient’ to a person dealing with a ‘problem condition’. This re-framing made a whole world of difference. You saw the young person who throughout their life has had to live and learn to cope with their disease. They have had to advocate and mostly fight to get heard and get the care they deserve. Often they have been dismissed and inorder to prove their case have had to question and record each and every aspect of their care in the midst of being labelled ‘probelematic’. They were just trying to survive, live and not to be consumed nor defined by their illness, colour of their skin or their socio-economic status.

The system is not perfect, no system ever is but we can strive to make it fair. If we are aware of our own and others preconceived notions and challenge them instead of buying into them because it is easier and or helps us fit in, be part of the gang then we are one step closer to creating a fairer system, if not an almost perfect one.

Where do broken hearts go? A midnight reflection on mental health and mental health services within hospitals.

Patient in a hospital bed.

Everywhere you turn, you are reminded that we are living in unusual times, with words like “unprecedented” banded around often. We are also reminded of self care and mental well-being due to the effects of the pandemic and lock-down changing our way of lives for the foreseeable future if not forever- whats being called “the new normal”.

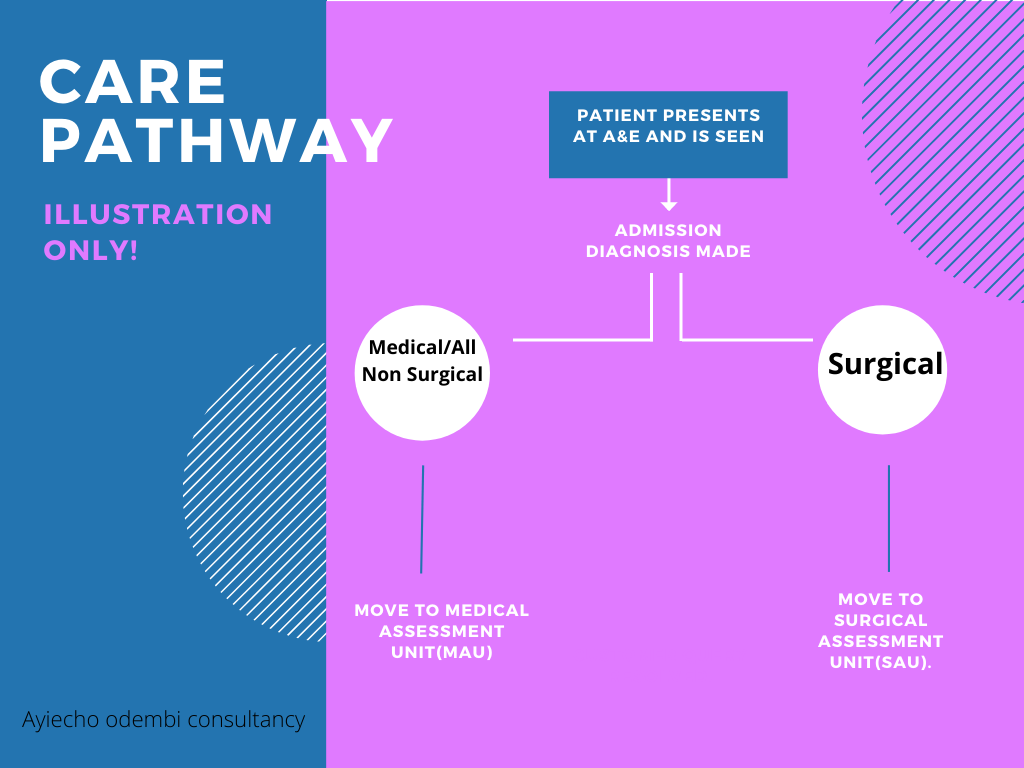

So there i was in the middle of the night, sleep having escaped me and Whitney Houston’s song ‘where do broken hearts go?’ playing over and over in my head, wondering where patients who presented with mental health problems went after coming into A&E? Or why , in my all my years in nursing, the only times i came across a mental health nurse was at university and when a psych consult was ordered on the unit/ward. Typically, when patients presented in A&E, and need admission, there are two routes normally followed- admission to the Medical assessment unit(MAU) or to the Surgical assessment unit(SAU). Most mental health patients end up in MAU or poisons unit( if admitted due to overdose and where such a unit is available and has empty beds).

Most of the time i have been involved in looking after a patient with mental health issues, it has been on an acute medical ward. This has been usually in the bays closest to the nurses patients reserved for patients who are acutely ill and need constant nursing supervision, which often involves bright lights, regular vital sign monitoring and other checks as per care plan with a hive of activity going on around due to the nature of varying acutely ill patients around. This got me wondering if an acute medical ward really is the right setting for someone going through a mental health crisis, given that they are being looked after by nurses, not mental health nurses, who yes might be doing a brilliant job and are good at what they do but are not aware of triggers or care pathways for someone going through a mental health crisis as a trained mental health nurse would with the patient in the right setting.

With a little help………

According to Mind¹, a leading mental health charity, mental health problems are common in England with 1 in 4 people experiencing some sort of mental health problem each year and 1 in 6 reporting having experienced a common mental health problem like anxiety or depression in any given week.

A study by The Nuffield Trust² looking at hospital use by people with mental health illness, makes for an interesting and sober reading and highlights a number of key points that need addressing. With almost every NHS hospital trust having a Medical assessment unit or a Surgical one, maybe it is time there was also a Mental health assessment unit where those coming into hospital with a mental health illness can get the care they deserve, looked after by trained mental health staff under conducive conditions designed with them in mind. I would certainly welcome a unit like that, where me and my fellow healthcare workers can pop into just for a chat or to make sense of life and all its challenges especially after a hard and emotionally draining day at work given the pressures we are constantly under with the added effect that this pandemic adds to it and i would be happy to know that mental health just like physical health, matters and that those going through any sort of mental health illness can come into hospital knowing that they have a dedicated area that’s ready to to help them in anyway possible.

Dr. Chisholm - the first Director-General of the World Health Organisation (WHO)